Closing The Deal on Concurrent Development of a Printed Circuit Board Layout

The restaurant industry has a saying, “Time to lean is time to clean.” The gist of it is that there is never a dull moment while the clock is ticking. Bearing in mind the importance of time, the PCB Designer is often faced with the prospect of starting a layout before all of the necessary data is on the table. A preliminary schematic and a rough outline are a step in the right direction but by no means the whole story.

That beginning may have been delayed while the schematic capture gets to a state where you have enough information to actually start the physical design segment. In the meantime, it’s always a good idea to inquire about any new connectors or other components so you can get a jump on obtaining or creating the footprint for the library. These kinds of things are often left to the Designer. Going to see the cognizant engineer or at least chatting them up will let them know that you’re on the job and are trying to push forward.

Figure 1. The ECAD station is a pivotal location for creating embedded technology. It may look artistic in the end but a lot of churn is likely to happen before the whole team is on board. Image Credit: Author

The Electrical Engineers and Mechanical Engineers can be spread quite thin with a lot on their plate. It can seem that they have a high tolerance for risk when it comes to the schedule. That is to say anything and everything can change at any time. The one exception is the tape-out date. This is the significant difference between a “waterfall schedule” and concurrent design.

Concurrent Design vs. a Waterfall Schedule

A waterfall schedule, if you didn’t know, is where one task is completed before the next one begins. Concurrent Design stands this notion on its head. This makes it more difficult for the PCB Designer to be able to commit to a tape-out date. In terms of schedule, the boss wants your best guess up front and they don’t want to hear a bunch of qualifications and conditions along with the estimate. That’s if they even ask you for your opinion in the first place. If that’s the way you’re being treated, you have to speak up for your own interests.

My previous role in Quality Assurance put me in a space where I was comfortable with statistics. My estimates would come with a confidence interval. Project Managers like to believe that nothing will go awry along the way. That means they want to assume the best case scenario as far as getting to the end of the job. I’d think to myself, “Trust me, Charlie Brown. Lucy is going to pull that football away at the last moment and you’ll end up on your back.”

I provide the best case date as the baseline with an uncertainty factor that shrinks away or solidifies as the job comes into focus. When the Program Manager emails the team and asks for a status update, I want to be the first one to provide my input. Drop whatever I’m doing and answer that question to send the message that I’m taking their concerns seriously.

One thing to have in your pocket for this situation is what the real estate industry calls Comps - or comparables. What did similar buildings in the area sell for in recent times? How long did a similar board take including all of the twists and turns? We all have a portfolio of board designs under our belts. Use this type of data to manage expectations. Pin counts, layer counts and board size are three main factors in the estimate. A solid memory of the nonlinear path to success is a good tool to have.

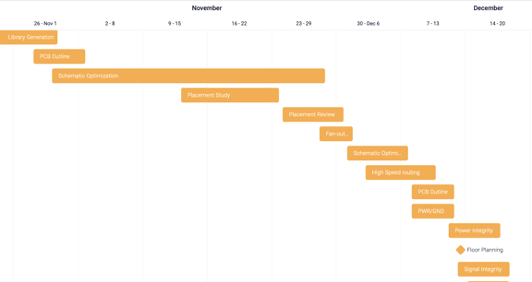

Special circuits like DDR memory have their own place in the estimate. Those types of circuits are easy to place but harder to route due to the length matching and other signal integrity concerns. Just creating the design rules for the specific subcircuit can eat a day. It may help your cause to sketch out a Gantt Chart showing various gates that you have to pass through to complete the project.

Figure 2. A Gannt chart showing the anticipated pace of the PCB layout flow from Library generation out to the final act. Just imagine a different timeline where the schematic optimization runs into mid-December! Image Credit: Author

Using the Divide and Conquer Method of Creating a Schedule

Breaking the schematic down to individual pages helps create a more detailed and plausible placement cycle. Page one might be the first block of the big chip with more pages to follow. Placing “U1” in the middle of the board gets you through a few pages with the heterogeneous gates taking entire pages with rectangles with about 100 pins each. Then you get entire pages full of bypass caps, each with their own pin assignment to support the SOC.

You know that any analog blocks are going to be iterative. Power delivery can be controversial as well. These types of circuits are easier to do when the board is uncrowded. Factor in more time for higher density. The main reason is that any new components will have a larger impact when there’s nowhere to put them. Having SI/PI people in the loop is sure to cause at least one extra iteration, maybe more depending on complexity.

The Boundaries of Time and Space

I don’t know how many times I’ve had to explain that I can take time and I can take space but I cannot make either of them. In fact, it takes time to take space. The number of times that an “improvement” resulted in fewer parts or fewer connections is rather small compared to the additive changes. I do like to think of any changes as improvements; easier to deal with that mindset with the difference simply being one of vocabulary.

As with placement, the routing cycle can also be broken down using the schematic one page at a time. When the whole job is characterized as a series of smaller tasks, it becomes clear when progress isn’t keeping up with the plan.

When the Best Planning Goes Off the Rails

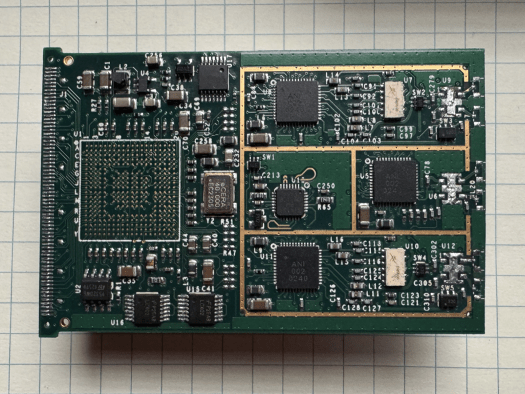

One time, I taped out a MIMO WiFi board including everything we knew at the time. The boards came back just like we ordered them. The people doing the bring-up discovered a spur, a spurious signal from one of the radios. This was enough to prevent the board from passing FCC certification as it would not make a good neighbor to nearby electronics. It cannot be shipped out to the service providers that way. The schedule didn’t have enough of a buffer for a respin but we had to do the best we could to recover.

The test tech and the EE pulled an all-nighter and were still there when I came in at 7:00 in the morning. Their overnight solution was to add a long skinny stub to one of the lines and situate it right where a handful of components resided. All of the affected components were up to me to place and route. To my eye, those became like new components even though there was no schematic improvement.

Figure 3. A MIMO radio with the baseband chip and the connector removed. This is similar to the one with the emissions problem. This card was plugged into laptops to give them a wireless connection. After Qualcomm bought the company, the circuit was consolidated onto a single chip with multiple matching networks and antennas to be used to turn your smartphone into a WiFi hotspot. Image Credit: Author

That became my 12-hour Friday and an 8-hour Saturday to get back to square one. The difficulty was to preserve the circuits that were passing muster while finding a home for the displaced components. That lost week fell primarily on the test techs but we spent what money we could to expedite fabrication and assembly.

A More Hypothetical Example of Making it Happen

Let’s say you got the job done a few days before it was set to go out. Further, let’s assume that the schematic is in its final iteration and you’ll get the final, final netlist the day before tape-out. That’s when you get what you wanted from day one. Let’s further suppose that the mechanicals are frozen at this point so they can’t give or take anything. The script could be flipped on another board.

What can we do to “grease the skids” on this project? Of course, we’d like to just stare at the layers to find any potential problems that are not covered by the design rules. We could also scrub the board for anything that can be brought under control with the constraint manager. We have reports we can run to find dangling lines or other electrical issues. There are some things that fall outside the scope of the Design Rule Checker. A little sliver of ground plane that has no via to support it may be found just through eye-balling the design. Routing under a fiducial mark might have slipped through. There are just so many little things that can go wrong.

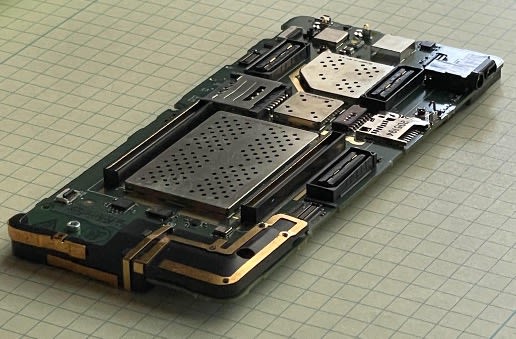

Figure 4. Some boards are an electro-mechanical nightmare. It takes time to ensure coexistence while meeting goals around placement and routing. The interdependencies of the circuit and interfaces cause us to depend on those around us to get to the finish line on time. Image Credit: Author

When you’re satisfied that the metal layers are all compliant, I’d go ahead and make artwork. That might be the moment when you notice that the silkscreen has the wrong revision or whatever. It’s also a chance to change the rev to zero and put the word “PRELIMINARY” in a huge font on the fab drawing. Do a full tape-out of the data and send it out to the vendor to get a quote and a DFM report.

Using Soft Power to Lead the Leaders

That might be someone else’s job and you should not step on their toes. If that’s the case, you can still forward the send-ahead data to the procurement team. This will allow them to notify the fabricator that there is an incoming job. The fab shop, in turn can make sure they have material or suggest alternate material if they were not already aware of this job. Even if that is a non-starter, just sending the preliminary data to the EE/ME groups can be a signal that they are the ones holding up the show.

That’s called using “soft power”. You have no authority but by being visibly out front of the team compels them to try to catch up. You’re not saying that explicitly, not even obliquely. You’re just giving everyone a status report. I like to make a list of three to five things but sometimes, it’s a single issue that is holding us up.

In most cases, being above board and proactively pointing out issues AND potential solutions in a digest form will help keep the job on track and ensure that they all know that you’re doing your part. The alternative is to be in continuous fire fighting mode. Eventually, you could end up getting burned by that approach. Keep cool, lead by example and help everyone get the job done. We either shine or stink as a unit. Opt for that first option!